Growing up in Minnesota in the 1930s and 1940s, I thought limpa, Swedish meatballs, potato sausage, boiled potatoes, pickled herring and jelly rolls were American food. We never ate chili when I was a child: we ate brown beans. We were Lutherans and we said “Ya,” not “Yes, Ma’am” to our teachers. I grew up thinking most everyone ate and spoke as I did -- except I had a friend who ate sausages and sauerkraut. Why were we this way?

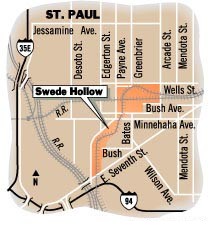

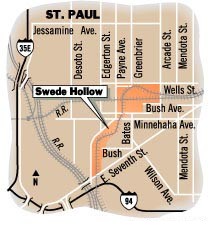

I’m a second generation American on my father’s side and it wasn’t until I was in high school that I began seeing the differences in ethnicity, for by that time the Italians had moved into my grandfather’s old neighborhood of Swede Hollow  and they were active and popular at our school. Yes, I grew up in a culture dominated by “Snoose Boulevard,” Borgstrom’s Drug Store, Dr. Johanson’s office, Carlson’s Jewelry store and Gustavus Adolphus church. But, becoming an adult started me thinking about my Swedish background and realizing the difference from many others and it was interesting to study and experience in greater detail.

and they were active and popular at our school. Yes, I grew up in a culture dominated by “Snoose Boulevard,” Borgstrom’s Drug Store, Dr. Johanson’s office, Carlson’s Jewelry store and Gustavus Adolphus church. But, becoming an adult started me thinking about my Swedish background and realizing the difference from many others and it was interesting to study and experience in greater detail.

Many Swedes immigrated to the Midwestern United States during the period 1860-1930 and a great number settled in rural areas to become property owners of farms or forest land. They carried Swedish traditions of the times with them and lost or modified some as they became assimilated into American culture. Swedish traditions are thought to appear strongest in rural areas, a few urban areas plus areas with organizations encouraging the practice of these traditions.

My plan for this study was to examine current practices related to Swedish customs in two or three predominantly Swedish heritage townships in the Midwest and compare the current practices to current Swedish traditions, discuss similarities and differences and then evaluate the possible reasons for differences. I have not tried to include urban areas like Chicago, Minneapolis, St. Paul or Seattle in this comparative analysis.

The intended methodology was to utilize the materials of the Swenson Center, select the two or three Swedish-American townships in the rural Midwest, develop a questionnaire to be used when interviewing persons or to be completed by interviewees and verify current Swedish traditions with contacts in Sweden.

It was anticipated that field work would be performed in rural townships in Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota. Selection of these areas would be made using resources of the Swenson Center, personal knowledge of the researcher and the roster of churches of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), because that is the predominant church of rural Swedish-Americans.

Research at the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center (Swenson Center) of Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois, other libraries including my personal library, and travel experiences in Sweden during the past several years provide an important element of this study. There were two departures from the original intent of the study. I did use some survey participants from the Rock Island area and I was not successful in utilizing specific congregations of Swedish-Americans in the study, thus, while this study remains rurally oriented, it may be more general than it would have been if I had successfully worked within congregations.

Preliminary research was performed at the Swenson Center in October and November, 1999. Field studies were also performed in a rural area of Illinois during November, 1999. It soon became apparent that some forces were in disharmony with the intent of this study. The presumption of the study that rural congregations with significant Swedish-American membership would form the nucleus of each study area proved invalid..

Initially, I thought it was just a lack of interest by pastors contacted of these congregations. As time went on, however, it became evident that the Institutional Church seemed disinterested in being associated with the study. It was clear that while individual pastors were willing to participate or discuss the study, there was an apparent lack of interest in encouraging participation in their congregations. At one point a pastor with two Swedish-American congregations (and one Norwegian-American one), suggested contacting the congregational relations unit of a church college to get information on Swedish-American traditions.

The study was modified to obtain an reasonable number of questionnaire responses. During July, 2000, field work was completed in Chippewa and Yellow Medicine Counties, Minnesota in a pocket of Swedish-Americans among Norwegian-Americans and Icelandic-Americans. A total of 35 questionnaires were completed by Swedish-Americans. The results indicate several interesting patterns and are summarized as an attachment to this paper.

What caused the Swedes to emigrate to America? There are a number of reasons. Stephan Thornton chronicles some of them in “The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups.”

“Overpopulation was the single most important long-range cause of Swedish emigration.” The population doubled to 3.5 million from 1750 to 1850 and by 1900 had reached 5.1 million. The first population peak occurred in the 1820s and is attributed to three primary factors:

- Lengthy period of peace,

- Availability of the smallpox vaccine, and

- Cultivation of potatoes.

This resulted in many young people looking for work 10-20 years later and therefore the need for emigration. “By the beginning of the era of mass emigration (1870), almost half - 48 percent - of the farm population was landless. Since industrialization began late in Sweden, the economy could not absorb the many unemployed and landless agrarian workers.” This was combined with the last country-wide famine in Sweden, in the 1860s, and the new program of readily available land in the United States by government patents or railroad grants to settlers. The call of America was strong.

In 1890, Swedes were two-thirds rural dwellers in the United States. That was reversed in only twenty years, when two-thirds of the Swedes became urban dwellers. Interestingly, by 1920, Swedes and their descendants owned more farmland in the United States than all the arable land in Sweden.

The Rev. L. P. Esbjörn founded a Lutheran congregation in Andover, Illinois in 1850. It was to “become the mother parish of the Augustana Synod.” The Augustana Synod was formed in 1860 with 49 mid-west congregations and about 5000 members. This included Swedes and Norwegians. The latter left the Synod ten years later. It thus was then a wholly Swedish-American church body.

There was an early commitment to higher education by the Swedish-Americans. Augustana College and Theological Seminary was founded in 1860 and Gustavus Adolphus College in 1862. Other Swedish-American colleges include Bethel in St. Paul, MN (1871), Bethany, KS (1881), North Park, IL (1891) and Upsala, NY in 1893.

Thornton concludes, “Once the Swedish-Americans accepted the decline . . . . . of the Swedish language as largely inevitable, but not fatal, they could turn their attention to aspects of the Swedish heritage that would interest the American-born, especially those who did not speak Swedish.” A characteristic holiday was St. Lucia Day, celebrated on December 13. Today, many organizations combine this with a Christmas (jul) celebration, while families tend to maintain a separation of the activities in the home. Celebrations at schools or workplaces are uncommon in the United States today.

Victor Greene reflects on old-time folk dancing during 1920-50 and a thesis of Marcus Lee Hansen which states, “What the son wishes to forget, the grandson wishes to remember.” Greene concludes that the popularity of ethnic folk-dancing, ethnic music and old-time bands after World War I clearly revises Hansen’s notion that the children of foreign-born fully rejected their parents’ culture. He states that this group showed great enthusiasm for such music at the most intimate private family affairs, at large public occasions and when listening to the radio or records. He then concludes that a new ethnic folklore was formulated from the old. Bands playing ethnic tunes thrived during this time. Included were such favorites as Frankie Yankovic, Lawrence Welk, Whoopie John Wilfarht and Walter Erickson.

In the book “The Ultra Entrepreneur” by Willmon L. White, Swedish-American capitalist, Curt Carlson, in a move quite unusual in anyone’s concern for old-country tradition, arranged for his granddaughter, Diana Nelson, to wear a wedding crown used in the parish church of Carlson’s ancestors for some 300 years. Calrson maintained a life-long interest in Swedish roots, business and culture. He traveled there often and was presented the Royal Order of the North Star and the prestigious Linnean Award of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. His roots were in Småland (Nottebäck) and Värmland (Svenstorp in Sunne parish). Carlson was also an American patriot, having that same granddaughter dress as The Statue of Liberty at a family gathering to celebrate the statue’s centennial.

“The American-Swedish Handbook”, 12th edition, was consulted for traditional Swedish-American activities. Nearly 500 Swedish-related organizations are listed in the publication, but about 50 of them, government organizations, were excluded in my evaluation. No attempt was made to count activities and events such as meetings, board of director meetings, arts and craft activities, museums, archives, films or number of visitors.

Activities I surveyed in the Handbook of a Swedish-American cultural nature were counted and evaluated. The following activities were considered to be offered and utilized to a significant extent:

- Events with food: 80

- Midsummer events: 79

- Lucia: 55

- Christmas: 50

- Music: 44

- Lectures: 38

- Language classes: 30

- Dance: 28, and

- Bazaars: 15.

Kräftskivar (crayfish parties) are growing in popularity from my interpretation of the Handbook. A number of traditional activities continue to be observed, including: Pancake and pea soup dinners on Shrove Tuesday, Trettondag jul (January 6), Tjugondag Knut (January 13), Julgransplundring (an activity on January 13), Valborgmässoafton (April 30), Swedish National day (June 6), dopp-i-grytan dinners, and worship services. To a lesser degree, sponsorships to Swedish language camps, taping interviews with Swedish immigrants, tours of Sweden, genealogy seminars and activities, Swedish history classes also account for activities of these Swedish-American organizations.

As indicated, the major Swedish-American church denomination in the United States is the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). It was interesting that with the exception of Augustana College and Gustavus Adolphus College, in that denomination, there appeared to be a reluctance to enter into dialog and assistance with this study.

I contacted The Rev. Frederick Rajan, Executive Director of the ELCA’s Commission on Multicultural Ministries, concerning the inclusiveness of traditional ethnic groups in affairs of ELCA. He replied that the ELCA mission is to “go therefore and make disciples of all nations,” recognizing that in the United States about 25 per cent of the population is “a person of color” and in the ELCA about two per cent of membership “is of color.” He went on to say, “inclusiveness is not an exclusive ministry,” but must be “carried out by all of us, both Whites and people of color.” This, of course, is undisputed. Pastor Rajan also acknowledged the Swedish influence in Puerto Rico when they established an Hispanic ministry over 100 years ago. The unanswered question remains; “Is an effort being made to encourage the preservation of traditions of the ethnic groups who brought the Lutheran faith with them to the United States?”

The importance of the faith Swedish immigrants brought with them can be exemplified by the history of one church in Minnesota. This church, Strombeck/Salem, celebrated its 125th anniversary in 1998. It was formed as Strombeck church in the rural area of Sparta Township near Montevideo, Minnesota in 1873. It was named for the first secretary and the organizer (Strommer and Beckman). The first julotta service was conducted in 1883. The congregation maintained a Swedish language parochial school and conducted its services in Swedish until 1931 when every other service was in English. The congregation began sharing pastors with the town church in 1936. The last annual meeting of Strombeck church was in 1946 as it has now merged into Salem. The significance of the Swedish tradition is remembered by the relocation of a stained glass window, entitled “Behold the Lamb”, from Strombeck to Salem when the Strombeck building was dismantled.

The Swedish traditions remain at work in the congregation, but Isaacs reports that at a recent church dinner, it was chili and not Swedish meatballs served. Thus, the subtitle of this article.

Nordström’s study, which includes eating habits of Swedes in southern Sweden, is confined to the fifty year period beginning in 1870. This period is similar to the major period of emigration of Swedes to North America. One custom, brought to the United States, is that of förning. Förning is the practice of each family bringing food to the feast, which assists by cutting cost, labor and time in preparing for the feast. It thus helps in maintaining cooperation in the community.

She goes on to say that, “When people tell of everyday routines and festive customs, it is the material reality they communicate, rarely their thoughts and feelings. The factual descriptions can appear monotonous and devoid of real content, but it is the experience of the narrator that appears in practical, everyday habits and festive rituals. These self-evident things are not just facts, but also the world they lived in, the praxis in which they were so obviously shaped.” She concludes, “On one level, meals are an ingrained routine, but on another they are a stage on which people interact to show who they are and what they want.” It is, then, no great surprise that there has been a strength in the retention of many Swedish foods and that they are best evidenced at holiday times in the minds of survey respondents.

The Swedish language is not commonly used, being spoken on a daily basis in the homes of only 20 percent of the respondents. Most do not use the language at all or just at special events. One does not get an impression that it is used in conversation to any appreciable extent. About one-third of the churches still have some Swedish activities and about half of them sing Swedish hymns. Among the hymns mentioned, “Children of the Heavenly Father” was by far the most common hymn. Others include: “Day By Day With Jesus”, “The Pearly Gates Will Open”, “How Great Thou Art” and “O Holy Wings.” These are sung in Swedish only at special times, like Christmas. No one mentioned the Christmas hymns often associated with Christmas, such as: “Now we Light a Thousand Christmas Candles” (“Nu Tändas Tusen Juleljus”), “Now it is Christmastime” (“Nu det är Jul Igen”), “When Christmas Morn is Dawning” and “I am so Glad on Christmas Eve.”

Half of the respondents (18) never eat lutfisk but almost that many (15) eat it once per year. Akvavit was identified as an alcoholic drink by 27 respondents (77%). Genealogical work has been performed by 20 persons responding (57%).

Most of the respondents had traveled to Europe (23) and Sweden (22), indicating that at least one of their stops was where their roots lie. Not surprisingly, most traveled there last within the past five years. One had traveled to Sweden more than 25 times. Most had also performed some Swedish genealogical work.

I asked what kinds of foods were served at church dinners, and it was interesting to see the mix of ethnic and American in the responses. In order of commonality are: rice pudding, potato sausage, American, casseroles, meatballs, cookies, lutfisk, Jell-O, cheese (bond ost), potatoes, herring, lingonberries, salads, beans, hardtack, limpa, fish. Mentioned just once were: turkey, cheesecake (ostkaka), fruitsoup, ham, pork, oyster dressing, coffee, eggs, lefse, red cabbage, chicken, dessert and bars.

It is not surprising that most respondents traced their family backgrounds to the Götland region of Sweden. Most came from Småland (19), while a good number had roots in Västergötland (9), Skåne (7) and Östergötland (7). Others reporting roots from this region include 3 from Blekinge, 2 from “Southern Sweden,” and 1 from Öland. The Svealand region was represented by 6 who had Värmland roots, 2 from “Stockholm,” 2 from Uppland and one from Södermanland. Norrland had only two provinces mentioned, Jämtland and Gästrikland with one ancestor representing each.

Seasonal customs; the knowledge of them by Swedish-Americans and how they are observed here follow.

Advent

While Sweden is a secular country, there are Christian and old traditional customs still observed which are tied to Christian festivals. In homes across the country, the approach of Christmas is signified by people getting out their Advent candlesticks, covering them with moss and lingonberry sprigs and four candles, signifying the four Sundays in Advent. According to Swahn, the first candle is lit on the first Sunday in Advent and burned down to half its length. Each succeeding Sunday in Advent another candle is lit and burned. By the fourth Sunday, after the last candle is lit, the first one is burned right down and there is a “stairstep” of candles in the Advent “box.” This is quite similar to the custom here of a Advent log or round Advent wreath. These are commonly used in homes with a Swedish and/or Lutheran tradition. Swahn indicates that the custom came from Germany where the use of Advent trees was common and became widespread in Sweden in the 1920s. The stepped candlesticks can be seen in the windows of both homes and businesses in Sweden.

Another German custom adopted by the Swedes is the use of an Advent calendar and now called a Christmas calendar in Sweden. It is a relatively new custom in Sweden, having been introduced in 1932. One must surmise that the popularity of these calendars in the United States is due more to German influences than Swedish, since so few Swedes have immigrated since 1932.

A relatively new custom in Sweden is to attend church services on the first Sunday in Advent. This attendance is about as popular as the early morning services on Christmas Day (julotta).

The questionnaire indicates that a solid majority of Swedish-Americans have or use an Advent wreath (60%) and 57% use or have used Advent calendars to get ready for Christmas. Almost two-thirds of the respondents indicated they typically go to church or make a special effort to attend church on the first Sunday in Advent.

Luciafest

The 13th of December is Lucia Day in Sweden and around the world, but, it is especially Swedish; even though visiting Italians must wonder why Swedes celebrate the day dedicated to the Sicilian saint from Syracuse. The Swedish holiday has little to do with her according to Liman. Folk tradition has it that this date is the longest night of the year, perhaps in remembering the medieval calendar. Liman says that only men celebrated this festival with considerable food and drink in its early times. Documents in the late 1700s tell of young girls, dressed in white with crowns of candles in their hair, serving their masters and mistresses. Lorenzen indicates that it began as a family celebration in Västergötland and other western parts of Sweden.

After a Stockholm newspaper arranged a contest to choose a Lucia to represent the city in the 1920s, the custom spread rapidly. Not only is it practiced in homes, but also in businesses, clubs, schools, retirement homes, hospitals and voluntary organizations. Now, Lucias are found everywhere and, dressed in white with the candelabra headpieces and a red sashes bringing trays of coffee, saffron pastries (lussekattor) and ginger biscuits (pepparkakkor). Sometimes, the Lucia serves a mulled wine called glögg. The Lucia is frequently accompanied by a train of white clad attendants (girls wearing glitter in their hair and boys wearing tall paper cones with stars on them). All sing traditional Lucia and Christmas carols.

After the Reformation, the adoration of saints was prohibited; however some of them - particularly St. Nicholas - had special significance to children and the general preparations for Christmas. Nicholas Day is traditionally December 6th and it failed to take root in Sweden because of the events on December 13. It was “transferred” to the 13th (Lucia Day) because the Swedes had celebrated this day since medieval times where they would eat and drink up to seven breakfasts in a row to prepare themselves for the Christmas fast which began on the morning of December 13th. Lucia is connected with the Latin word for light, lux, and this festival is considered the festival of light when, according to tradition, the nights begin to grow shorter.

In the United States, many of these celebrations are associated with Swedish-American events and Christmas programs. A good number of communities choose a Lucia and publicly celebrate this day, often in the evening. About half of the questionnaire respondents knew about the Swedish fest, but very few observe any special activities on December 13. About a quarter could identify “Sankta Lucia” as a traditional carol for this date.

Christmas or jul

Most respondents (60%) decorate for Christmas between Lucia day and the weekend just preceding Christmas. This is not dissimilar from current customs in Sweden, according to Shwan. Both he and Lorenzen indicate that in Sweden the Christmas Eve meal starts with a smörgåsbord of various kinds of pickled herring, liver paste, smoked sausage, boiled pork sausage, pork roast, cold roast spare ribs, pig’s feet in aspic, ham, cabbage, meatballs, Jansson’s Temptation and limpa. This is followed by lutfisk in many homes. Lutfisk is a relic of the medieval Christmas fast where there was a fortnight of meatless meals and fresh fish were hard to obtain. Lutfisk is processed from dried cod or ling. It is alternately soaked in water and lye to make it plump and tender. The fish is finally boiled and served with a white sauce or melted butter and several spices. When the Reformation arrived in Sweden, there was little reason to eat lutfisk. It did, however, become a traditional part of the season and is still practiced almost 500 years later. Dessert consists of rice pudding and ginger snaps (pepparkakor).

Growing up in the midwest, I cannot recall ever seeing or tasting Jansson’s Temptation. I never saw it until I traveled to Sweden, but acknowledge that some Swedish-American associations may serve it, on occasion. It is especially common in Sweden and virtually non-existent here. For example; the Arlington Hills Lutheran Church (the first English-speaking Swedish Lutheran church in St. Paul, Minnesota) put out a cookbook; it has twelve fish recipes but none are for Jansson’s Temptation or lutfisk.

The Christmas season is celebrated in both countries and, not surprisingly, with some similar activities. When asked to identify the Swedish word jul, 83% answered correctly. Only six respondents did not identify this as our Christmas. A festive dinner or smörgåsbord, often accompanied with going to church, a family gathering and opening presents are predominant methods for Swedish-Americans celebrate Christmas Eve in the United States. This differs some from a common practice in the United States of opening all presents on Christmas morning. Other activities mentioned for Christmas Eve include some kind of program in the home, singing, reading scripture and poetry, dancing around the tree, listening to Swedish folk music, drinking, hanging the Christmas stockings, skiing and dressing for dinner . The practice of dopp I gryta (dipping bread in a pot of broth from the cooking meat) and eating lutfisk is still practiced here and is considered a highlight of the season by a number of respondents. Enjoying lutfisk is not restricted to Christmas Eve, but may be done at many places during the whole Christmas holiday season. Some restaurants even serve this “delicacy.”

On Christmas day, activities changed some. Celebrating with food and the gathering of family and friends were most frequently indicated in the responses, followed by: opening gifts and presents, getting Christmas stocking gifts, attending julotta (the early morning service), enjoying a big breakfast, relaxing, skiing, listening to Swedish folk music, going for walks, reading scripture and turning on the house lights early in the morning and evening. Only about one-third of the respondents identified julotta and it appears that it is not anywhere near as common as a century ago in Swedish-American communities. Some Salvation Army and Lutheran churches continue to offer this service, but it appears to be fading in both countries. This service still has special meaning to many midwesterners in the United States, especially the singing of “Var hälsad, sköna morgonstund”, which may be translated as “greetings this beautiful morning hour” and is traditionally sung at julotta services.

A solid majority, (74%) correctly identified a tomte (also known as a jul-tomte) as a gnome-like creature or troll who delivers gifts (like our Santa Claus) and 43% identified a julbock as a straw goat that carries the Christmas presents.

Some folks still observe twelfth night (January 6 - trettondagjul) and St. Knute’s Day (January 13 - tjugondag Knut) by taking down their Christmas trees but not much else happens at those times in the United States. This seems similar to what transpires in Sweden today, although, I think the similarity is by chance. One possible distinction is that Swedes still have a day off work on twelfth night, according to Swahn. Swedes do, however, celebrate on St. Knute’s Day. This is when Swedish families “plunder the Christmas tree.” It is called julgransplundring. The children, again according to Swahn, gather to strip the tree, now bare of most needles, and also to play games, eat cake and a fruit drink, throw out the tree and eventually walk home with a bag of sweets and other treasures.

Lent and Easter

The reasons for fasting during the forty days of Lent became less important for the Swedes after the Reformation, but some traditions have been retained. A custom in the United States brought over by Swedish immigrants is the eating a meal of green or yellow pea soup, Swedish pancakes and semlor, lightly cardamom flavored buns. In Sweden, these buns were often eaten with marzipan or in a bowl brimming with hot cream and sprinkled with cinnamon. Nowadays, they are more restricted to office coffee breaks and eaten plain. Very few Swedish-Americans now observe any special eating habits during lent or on Shrove Tuesday (the day before Ash Wednesday) and more widely known here as Mardi Gras, probably due to the celebration in New Orleans.

The questionnaire also asked about the current Swedish custom of decorating the house with birch twigs with colorful feathers tied or glued to them in the weeks leading up to Easter. These are called påskris. They are widely available in markets in Sweden and may be placed in water-filled vases thus forcing leafing of the twigs, according to Swahn. This custom is almost unheard of in the Midwest United States among Swedish-Americans.

The one aspect of this season familiar to Swedish-Americans was Påsk. Almost half of the questionnaire respondents could identify the word as the Swedish word for Easter. One difference between Sweden and the United States among those uninterested in the Church is that this day, Easter, results in a five-day holiday in Sweden, whereas it is typically only a two-day weekend in the United States.

Walpurgis and May Day

The evening of April 30 is widely celebrated by choral singing around bonfires and drinking. in Sweden and is known as Valborgsmässoafton. The Swedes wearing their white “student caps” do this to celebrate the coming of spring. May Day is a holiday in Sweden celebrating the labors of the people. This would be like Labor Day in the United States. May Day is not celebrated in the United States by Swedish-American respondents, probably because we have a different day set aside for acknowledging our labors and because May Day is a day associated with communism in the American mind and therefore rejected by Americans. Only two respondents to the questionnaire stated that they celebrated Walpurgis/May Day, but some stated they had formerly made May baskets, put flowers in them and hung them on their cousins’ doors.

Another example of observing this day is recorded by Birger Swenson in his book, “My Story.” “Following the Swedish custom of celebrating the 1st of May, the members of the Olaf Rudbeck Literary Society met for breakfast on Zion Hill (at Augustana College in Rock Island, IL) May 1, 1921. We enjoyed a Swedish breakfast menu: sill (herring), skinka och ägg (ham and eggs), smör och bröd (butter and bread) and kaffe (coffee). It was a happy occasion on a beautiful day. The members sang Swedish student songs and Professor Mauritzson commented on the first of May tradition in Sweden. Later we all had a second cup of coffee during which time, Professor Mauritzson enjoyed his pipe.”

Midsommar

One of the biggest holiday celebrations of the year in Sweden is midsummer’s day which is celebrated on the Friday and Saturday closest to June 24. It is a holiday where everyone wants to be in the countryside to celebrate the long days of summer. The amount of daylight varies from over 18 hours in the south to 24 hours in the north of Sweden, according to Svensson. The Maypole (majstång or midsommarstång) is decorated in the morning with fresh flowers and bows and is raised for the community (or in a family’s garden). When the Maypole is erected, the children sing songs and dance traditional games. Everywhere they pretend to be small frogs and other animals. Before long, they are joined by the adults. Often, when a small community gathers, there is live folk music for the afternoon. As the afternoon moves toward evening, the adults play games, go visiting in the community and enjoy a fest which may include, boiled dilled potatoes, several kinds of herring in sauces, beer and akvavit, and perhaps, strawberries and cream. After the meal, parties and dancing continue, often until dawn (which may come at 3 AM in the south).

Most (66%) of the questionnaire respondents do not engage in any special midsummer celebration. There are, however, many Swedish-American organizations which do. These can last from a couple hours to ten hours, complete with a Maypole, music and plenty to eat and drink. Here it seems to be up to the old-timers to encourage the youngsters to dance around the Maypole. This is one time of the year when traditional Swedish clothing is worn by the adults and where they can show their county or provincial heritage to the gathering.

Crayfish parties

The end of summer in Sweden is observed with a number of crayfish parties (kräftskivar). The end of summer comes early in Sweden as the children return to school in early August and these crayfish parties are frequently held about the 7th to the 10th of August (some say they should be held the night of the first full moon after the crayfish season starts). Kräftskivar are remarkably similar whether at the Carlsson’s, Moding’s or Andersson’s homes. A large lighted paper moon hangs in one corner of the room, a mound of crayfish with dill is prepared and served along with drinks of all types, soft-drinks, beer and many skåls with akvavit preceded by a little song. The partying goes on for hours and all settle in for a festive evening by wearing bibs with a crayfish motif and funny hats. This appears to be a relatively new and greatly enjoyed custom in Sweden, but Svensson reports that it began over a hundred years ago.

In the United States, very few crayfish parties are held, but they are becoming more popular. This does not seem to be a custom the immigrants brought over from Sweden, but brought back by recent American visitors to Sweden or Swedish-American organizations. The activity provides an exciting possibility for building this custom here. Groups such as FEST, (Friends Encouraging Swedish Traditions) a part of the

American Swedish Institute of Minneapolis, use it as an opportunity to encourage young adults to become interested in this and other Swedish customs.

Questionnaire respondents, for the most part, did not show an inclination to have crayfish parties. Seventy-seven per cent did nothing in the way of celebrating or weren’t aware of crayfish parties.

St. Martin’s Day

In the province of Skåne, November 10th (Martin Luther Day on the Swedish calendar) is a day celebrated as Mårtensafton, or the eve of Mårten’s name day (November 11). Nowadays, this evening is often observed on the Saturday evening before or after November 10. A mårtensgås (goose) is roasted and served after a goose blood and giblet soup (svartsoppa), according to Andersson. The meal is often completed with a special cake called spettekaka, which is a tall cake of egg yolks and sugar, baked on a spit and layered. This celebration originated in France in the 1500-1600s, moved through Germany and then arrived in Sweden. Svensson claims this meal which residents of Skåne eat with pride originated in a restaurant in Stockholm in the 1850s. This could make for lively dinner discussion in Skåne. Did it arrive from the south or from the north?

Again, this custom does not have many adherents in the United States as 77% did not know of it or celebrate it. It appears that the most knowledgeable were those who had ancestors who lived in Skåne. The foods those respondents associated with St. Martin’s Day are goose, svartsoppa, spettekaka and caviar.

Ethnic Influences

Questionnaire respondents were asked to rank influences in their lives concerning Swedish traditions. By far, the most significant influences were family members. All respondents who listed family as being important also listed them in the upper half of the ranking scheme. Twenty-six ranked family as first or second. There were some double rankings of the top influences. The second most important factor was the local church followed by church colleges. Swedish-American organizations and place of birth were both considered secondary to other influences. Neighborhood activities and residents had a tertiary effect. Other factors listed include: extended family, friends, stories, novels, Scandinavian design, sauna, family visits, loyalty to Sweden, Swedish heritage and finally, one respondent stated “many trips to the Holy Land (Sweden).”

Andersson, Lars Tommy & Kerstin, 1999,2000, Kivik, Sweden, personal correspondence and meetings

Carlsson, Elin Märta, 1999, Mölndal, Sweden, meeting

The American-Swedish Handbook, 12th edition, 1997, Swedish Council of America, Minneapolis, MN

Favorite Recipes of Arlington Hills Lutheran Church, about 1970, Arlington Hills Lutheran Church, St. Paul, MN

Greene, Victor, 1990, Old-time Folk Dancing and Music Among the Second Generation,

1920-50, from American Immigrants and Their Generations - Studies and Commentaries on the Hansen Thesis after Fifty

Years, Edited by Peter Kivisto and Dag Blanck, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, pp 142-163

Isaacs, Alton and Rudell, 1999, 2000, Clarkfield, MN, personal correspondence and meetings

Liman, Ingemar, 1983, Traditional Festivities in Sweden, Swedish Institute, Berlings, Sweden

Lorenzen, Lilly, 1964, Of Swedish Ways, Dillon Press, Minneapolis, MN

Moding, Philip & Ingegärd, 1999, 2000, Malmö, Sweden, personal correspondence and meetings

Nordström, Ingrid, 1988, Till Bords (At Table), (English summary of the chapter “Everyday morality and festive prestige in southern Swedish peasant

society”), Doctoral dissertation, Carlsson Bokförlag, Lund, Sweden, pp 226-236

Rajan, Frederick, 2000, Chicago, IL, personal correspondence

Strombeck/Salem Lutheran Church 125th Anniversary Program, Growing In God’s

Kingdom, 1998, The Ink Spot, Clarkfield, MN

Svensson, Charlotte Rosen, 1996, Culture Shock, A Guide to Customs and Etiquette -

Sweden, Graphic Arts Publishing Co., Portland, OR

Swahn, Jan-Öjvind, 1997, Maypoles, Crayfish and Lucia, Fälths Tryckeri, Värnamo, Sweden

Swenson, Birger, 1979, My Story, Augustana Historical Society, pp 53-54

Thornton, Stephan, editor, Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic

Groups, Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA, 1980. pp 972-980

White, Willmon L., 1988, The Ultra Entrepreneur, Gullets Pictorial, Inc.

and they were active and popular at our school. Yes, I grew up in a culture dominated by “Snoose Boulevard,” Borgstrom’s Drug Store, Dr. Johanson’s office, Carlson’s Jewelry store and Gustavus Adolphus church. But, becoming an adult started me thinking about my Swedish background and realizing the difference from many others and it was interesting to study and experience in greater detail.

and they were active and popular at our school. Yes, I grew up in a culture dominated by “Snoose Boulevard,” Borgstrom’s Drug Store, Dr. Johanson’s office, Carlson’s Jewelry store and Gustavus Adolphus church. But, becoming an adult started me thinking about my Swedish background and realizing the difference from many others and it was interesting to study and experience in greater detail.